Oh

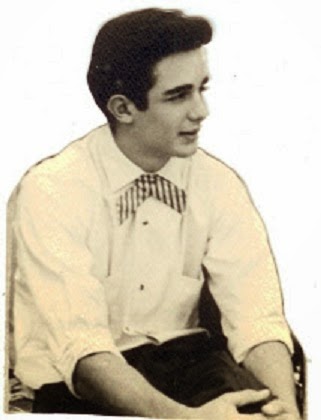

Captain...My Father Emilio Torres.

By Arlette

Torres

I am 12 year

old again. It is Mexican time. Eternal illusion. Past, present, future

suspended in amber.

My father's

hand grasps mine. We walk briskly on a busy street in Torreón Coahuila, México.

Ahead, an

elderly blind man sits on the filthy sidewalk outside a shoe store. He asks for

metal mercy, copper confetti. The man holds a can between his ruined brown

hands, crumpled like ancient parchment paper.

The young

thug came like a left jab. Boxers work in milliseconds. He kicked the can from

the old man's hands. I didn't see the blow. I heard the guy yell:

"Gooool!" The thug ran. His blasé cruelty remained, thickened the air

and made ribbons of my entrails.

The elderly

man sat. Blind. His hands shaking softly while coins flew everywhere. The sting

of his humiliation slit my eyelids. Tears welled between my skin and my soul.

Before water spilled, my father sprang forward. Feral speed. Fierce grace.

Senses refined. I saw my father become deadly. He excreted ferocity. I felt

lightheaded; didn't want to see what came next.

But my

father didn't chase the thug. Instead, he kneeled next to the blind man.

I went

looking: around the newspaper stand and the lottery stand and the phone booth.

The coins would not be reclaimed. They became part of the filthy pavement. The

blind gentleman lost. Then my father gestured. "Come here, Arlette."

He pulled me down, held the old man's hands between his own. Then he

leaned forward and whispered in his ear. Those pupils, veiled and milky bluish

danced they danced... he was alive.

Dad handed

me something round, cold. He told the elderly man, "Don Eufrasio this is

from my daughter. Take it and go home. I'll be watching." I squeezed the

thing, placed it between those ancient palms, the cartography of our suffering

collected in each deeply etched line. His skin was thick though, not delicate.

He held on to my fat square hands. I waited. My father added his hands around

mine and he knitted the tears that were and would be.

We stood up,

walked away quickly hand in hand. Stopped at the corner. I looked back. Don Eufrasio

sat on his cardboard. He was beautiful, petrified, luminous. His face remained

turned toward us. Could he see us? Yes he saw us and then through us and beyond

to a place only he knew.

Dad smoked.

We waited. A couple of hours passed. Finally Don Eufrasio's grandson came to

collect his grandfather, who tripped over words, yelling, smiling, shaking

disbelief from his dry bones. The young man looked over at us. He nodded,

discombobulated by his grandfather's wild gestures. They left. We

left. Dad drove slowly. I broke the

silence. "Papá, is Don Eufrasio your friend?" My father looked over

and smiled with sad divinity. "Don Eufrasio was not my friend. But now we

are. His friends."

At home, my

mother scrutinized dad. Something was missing. Aha. She finally knew what was

off.

"Emilio

where is that ghastly gold Centenario you hang from your keychain?" Dad's

Centenario, that cold, round thing. A fifty peso solid gold coin bearing the

Angel of Independence, worth around $2100 dollars today. Dad looked at her.

"Oh I got tired of it. I sold it. Gold prices are good." My father

lied. My mother

believed. I kicked ethics in the teeth. "Good. I don't know why you like

to use them as keychain charms. They're so vulgar...ostentatious really."

That night

my father sat across from me, elbows on his knees. He seemed somehow different.

Human. Tired. Small. Beautiful leviathan. Endless. His eyes filled with crystalline

belief and spoke:

"Never

sell something you can give away Arlette."

My father

died two years later. I was fourteen. His death the guillotine of my life.

Before and after.

Don Eufrasio

is also dead. I am 42. My hands are dirty and empty. Yet sometimes I feel pure

because my father comes to fill them. I cup them tightly around his endless

pour and then spread my fingers, giving it all away.

No comments:

Post a Comment